A minor change control has been approved, impacting only a small section of the network. However, the change is performed on shared network infrastructure such as firewalls or load balancers. Now comes implementation time, which is the ideal time for application usage but miserable for operators that value their weekends or evenings. Preparation is everything, the appropriate IT staff is on hand to conduct the change and the right business validators set to ensure success. Nothing unusual here and then…BAM! Something goes wrong. The NOC is inundated with calls and management system is lighting up like a Christmas tree.

Gulp! You now have a priority one with multiple production apps offline. One by one middle managers join the war-room bridge, each demanding the same repetitive debrief. The next hour is spent explaining what is going to be done about this, rather than of course, actually doing anything.

This scenario has happened to most all of us. For most organizations, the solution is to include more teams in the planning and execution of future changes. Soon the organization has half its staff “supporting” changes in case something goes wrong.

This scenario often leads to excessive risk aversion, leaving an organization paralyzed while competitors adopt cutting edge technology. Some companies take weeks or longer to roll out basic changes to an application or network, while other nimble companies and shadow IT groups are able to continuously adopt, change, and succeed.

One way is to address root causes that breed risk paralysis is to limit high capacity, monolithic, single points of failure. Typically core infrastructure such as routers and layer three switches are fairly stagnant when it comes to change. The majority of changes on a network are generally closer to the application or at the edge of the network. Often architectural designs force changes that extend too far into the network infrastructure rather than at the edge. For example, a firewall rule for an app resides on a firewall that all application traffic must pass through. A load balancer proxying all applications creates a similar single point of failure. Aggregated appliances, particularly those residing higher in the OSI layer, are ripe for catastrophic failures as they are the most frequently changed components in a network.

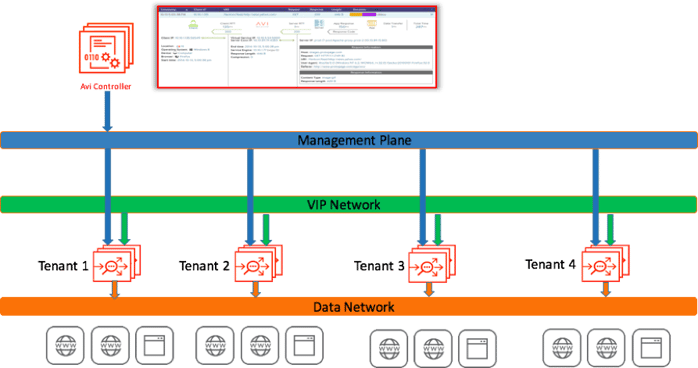

Cost has historically made it prohibitive to horizontally segment applications or tenants on network infrastructure which would help limit the “blast zone” of failures. To make things worse, often we have to purchase large, expensive appliances that need to have the capacity to support ALL of the aggregate traffic traversing the network to the application servers at the edge. Some manufacturers have tried to address segmentation issues by developing contexts or administrative partitions to help isolate management functions. This is like putting a white picket fence around your house and expecting it to protect you when your neighbor's house blows up. It does not provide guaranteed isolation.

The solution is straightforward. Separate the management from the data plane. Dynamically create, configure, and resize the data plane on demand. Central management provides a single point of control, which minimizes configuration complexity and may still be layered with tenant isolation.

By limiting the blast radius of a config change gone awry, each application can have its own change control window. Higher SLAs are achievable through dedicated infrastructure. This is central to the rise of software defined networks, which have found that modern architectures can bring better availability, scalability, and most important, happier operators. SDN is not about layer two connectivity, it's a way of interconnecting, automating, and modernizing.